The list represents the best, the list is life, and outside the list is death.

“Schindler’s List” has been described as a film about the Holocaust, but the Holocaust provides the venue, not the theme, for the story.

The film is actually a study of two parallel characters – one a con man and the other a psychopath. Oskar Schindler, who defrauded the Third Reich, and Amon Goeth, who represented pure evil, were both created by chance.

Schindler was not commercially successful both before and after the war, but he used his cover to open a factory that saved the lives of more than 1,000 Jews. (Technically, the factories also failed, but that was his plan: “I would be very unhappy if this factory produced a shell that could actually be fired.”)

Goeth was executed after the war as a cover for his murderous pathology.

In telling their story, Steven Spielberg found a way to approach the Holocaust, a subject too vast and tragic to cover in a novel in any reasonable way.

In the rubble of the saddest story of the century, he finds, not a happy ending, but at least an affirmation that resistance to evil is possible and successful.

In the face of the Nazi mortuary, we must make a statement, or we will fall into despair.

The film is an easy target for those who think Spielberg’s approach is too optimistic or “commercial,” or condemn him for turning Holocaust material into a good story.

But every artist must work in his medium, and unless there is an audience between the projector and the screen, the medium of film does not exist.

Claude Lanzmann made a deeper Holocaust film in “Shoah,” but few would have the patience to watch the nine hours.

Spielberg’s unique ability in his serious films is to combine artistry with pop – saying what he wants to say in a way that millions of people want to hear.

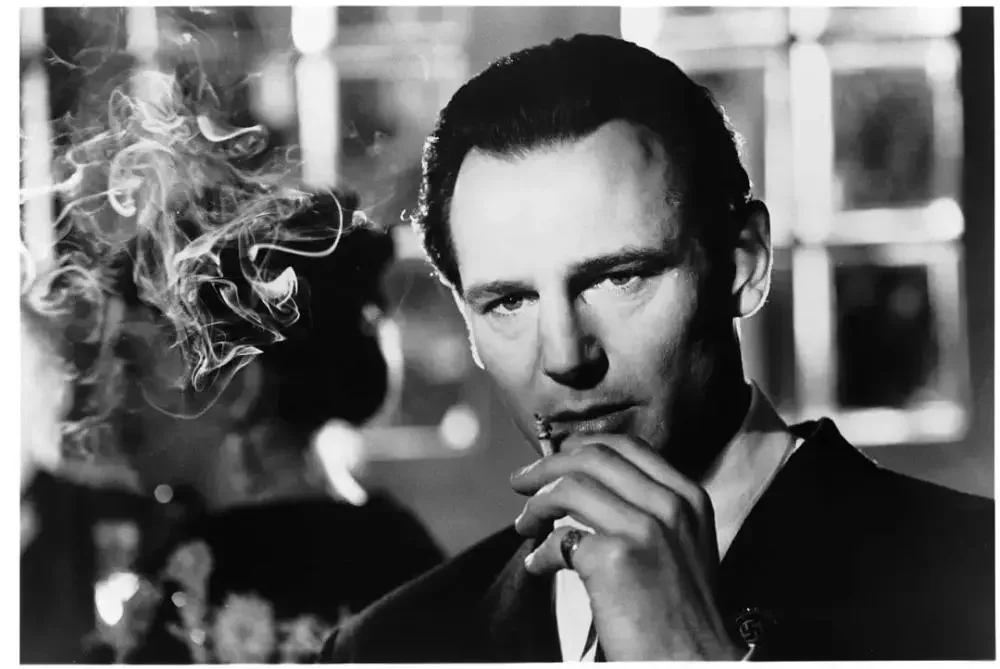

On “Schindler’s List,” his greatest achievement was the role of Oskar Schindler, played by Liam Neeson, a man who wouldn’t admit to anyone what he was doing until the very last moment.

Schindler leaves it to “his” Jews, especially his accountant, Itzhak Stern (Ben Kingsley), to understand the unspeakable: Schindler is using his factory as a hoax to defraud the Nazis of his workers life.

Schindler left it to Stern, Spielberg left it to us; the film is a rare case of a man doing the opposite of what he appears to be doing, and the director leaves the audience to figure it out for themselves.

Schindler’s audacity is amazing. His first factory made pots and pans, and his second-hand made bullet casings. Both factories were inefficient and contributed little to the Nazi war.

A more cautious person might insist that these factories, producing beautiful jars and usable casings, were invaluable to the Nazis.

The whole reason for Schindler’s obsession is that he wants to save Jewish lives and produce useless goods — all while wearing a swastika on the lapel of his expensive black-market suit.

The key to his character lies in his first big scene, in a nightclub frequented by Nazi officers.

We speculate that his resources include the money in his pockets and the clothes he wears. He walked into the club and served a table of high-ranking Nazi officials with the best champagne, and soon there were Nazis and their girlfriends sitting at his table, swelled with late arrivals.

Who is this guy? Why, of course Oskar Schindler.

Who is that? The German Empire never found an answer to this question.

Schindler’s strategy as a liar was to always appear to be in power, appear well-connected, and give powerful Nazis plenty of gifts and bribes. And he swaggers, arrogant, through situations that would crush the weak.

He also has a knack for tricksters to disguise the real object. The Nazis accepted his bribe and believed his purpose was to enrich themselves through war.

They did not object because he enriched them too. It never occurred to them that he was actually saving the Jews.

There is an old story of guards who search a thief’s cart every day without knowing what he is stealing. He was stealing the wheelbarrow, the Jew was Schindler’s wheelbarrow.

Some of the film’s most dramatic scenes show Schindler snatching his workers from the abyss of death as he rescues Stern from the death train.

He then moved a train of male workers from Auschwitz to his hometown in Czechoslovakia.

When the women’s train strayed into the Auschwitz concentration camp, Schindler bravely strode into the death concentration camp and bribed the commander to transport them out again.

His insight was that if he wasn’t real, no one would have walked into Auschwitz with such a mission, and his audacity was his shield.

Of course, Stern soon discovered that Schindler’s real purpose wasn’t to get rich, but to save lives.

However, it wasn’t until Schindler put together a list of some 1,100 workers who would be sent to Czechoslovakia that people were saying it out loud.

“This list is definitely a good thing,” Stern told him. “The list is life. It’s surrounded by bays.”

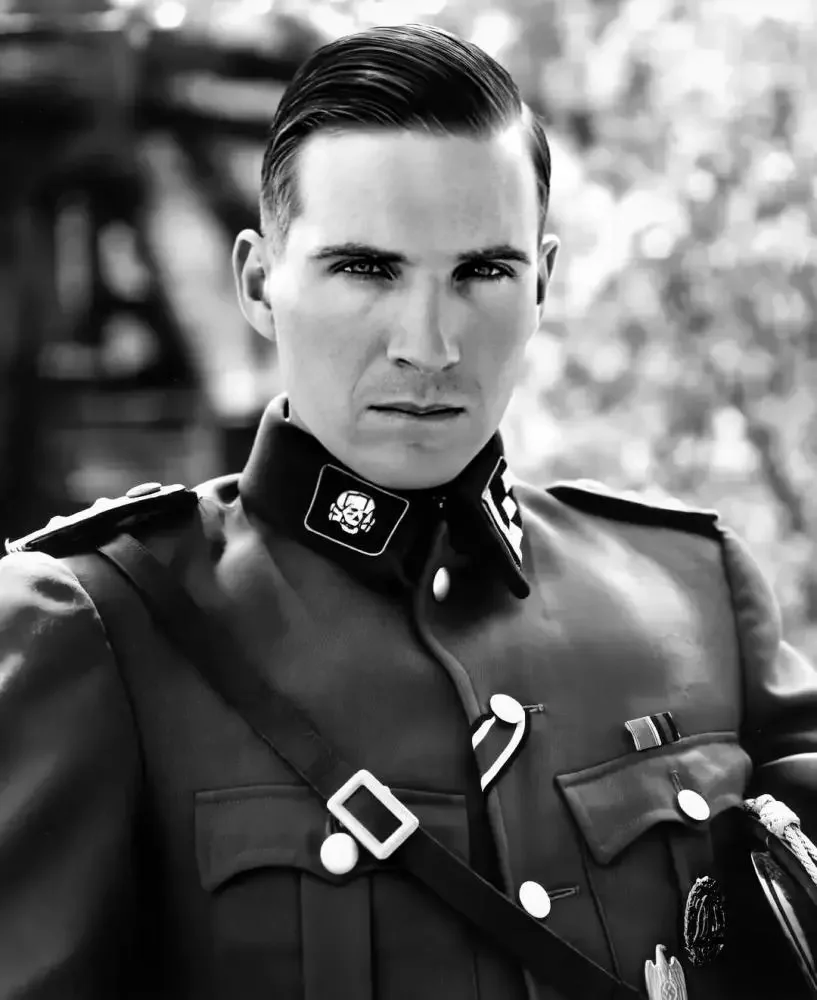

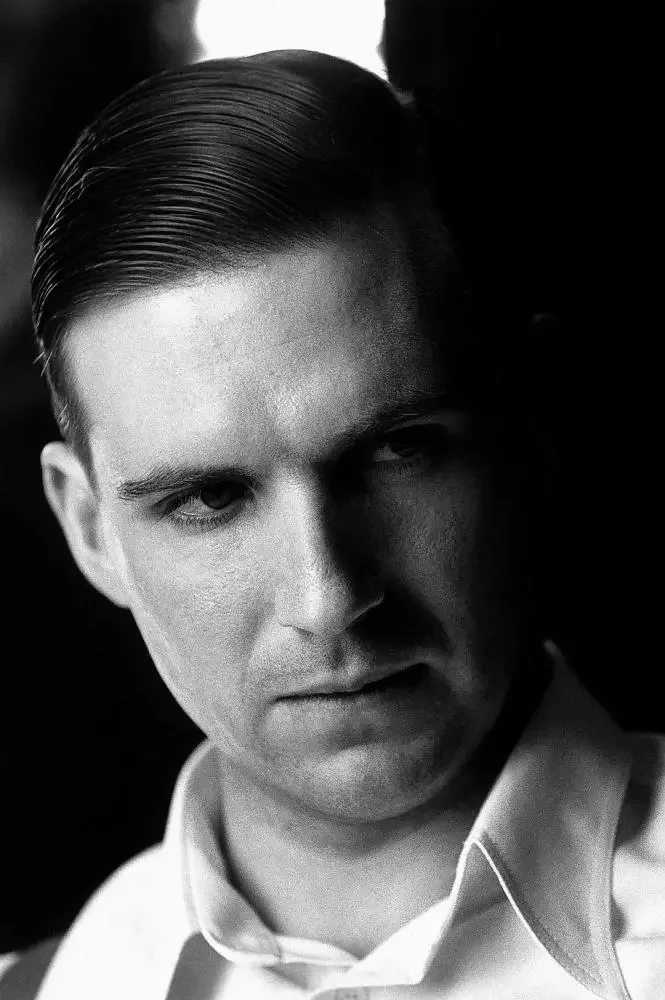

Now think about commander Amon Goeth (Ralph Fiennes), the Nazi who took control of the Krakow ghetto and later the concentration camp where the Jews were transferred.

He stood on the balcony of his ski cabin, shooting Jews as practice targets, destroying any hope they had that Nazi policy would follow some normal pattern.

Protesting and insisting are pointless and useless if they can die as they please.

Goeth is clearly insane, and the war obscures his serial killer nature. His cruelty in turn hurt his victims: he spared a life, giving only hope to his victims, and then shot him.

Saw “Schindler’s List” recently and wondered if it was a weakness that was driving Goeth insane.

Wouldn’t it be better for Spielberg to focus on a Nazi worker — an “ordinary” person who just obeyed orders?

The horror of the Holocaust was not because monsters like Goeth would kill, but because thousands of people were taken from their daily lives and, in chilling terms, became Hitler’s willing executioners.

Spielberg made this film unforgettable and heart-wrenching; maybe there is a need for a one-dimensional villain in a movie because the protagonist has so many hidden dimensions.

A regular guy who just “obeys orders” might distract from the focus of the film — though he’ll be contrasted with Schindler, a regular guy who doesn’t obey orders.

“Schindler’s List” gave us some information about how the Holocaust was carried out, but not explained, because it is puzzling that people would commit genocide. Or that we would like to believe.

In fact, genocide is commonplace in human history and is now happening in Africa, the Middle East, Afghanistan and elsewhere. The United States was colonized through a policy of genocide against indigenous peoples.

Religion and race are markers we use to hate each other, and unless we can rise above them, we must admit that we are potential executioners.

The power of Spielberg’s film lies not in its explanation of evil, but in its insistence that man can be good in the face of evil, and that good can prevail.

The ending of this movie brought me to tears. At the end of the war, the Jews of Schindler were stranded in a strange land – but alive.

A member of the liberating Russian forces asked them, “Isn’t there a town over there?” They walked towards the horizon.

The next shot fades from black and white to color. At first we thought it might be a continuation of the previous action, until we saw that the men and women on the top of the mountain now dress differently.

Then we suddenly realized: these were Schindler Jews. We are watching the real survivors and their children as they visit Oskar Schindler’s grave.

The film begins with a list of Jews imprisoned in the ghetto. It ends with a list of those rescued.

This list is definitely a good thing, the list is life and the bay surrounds its edge.