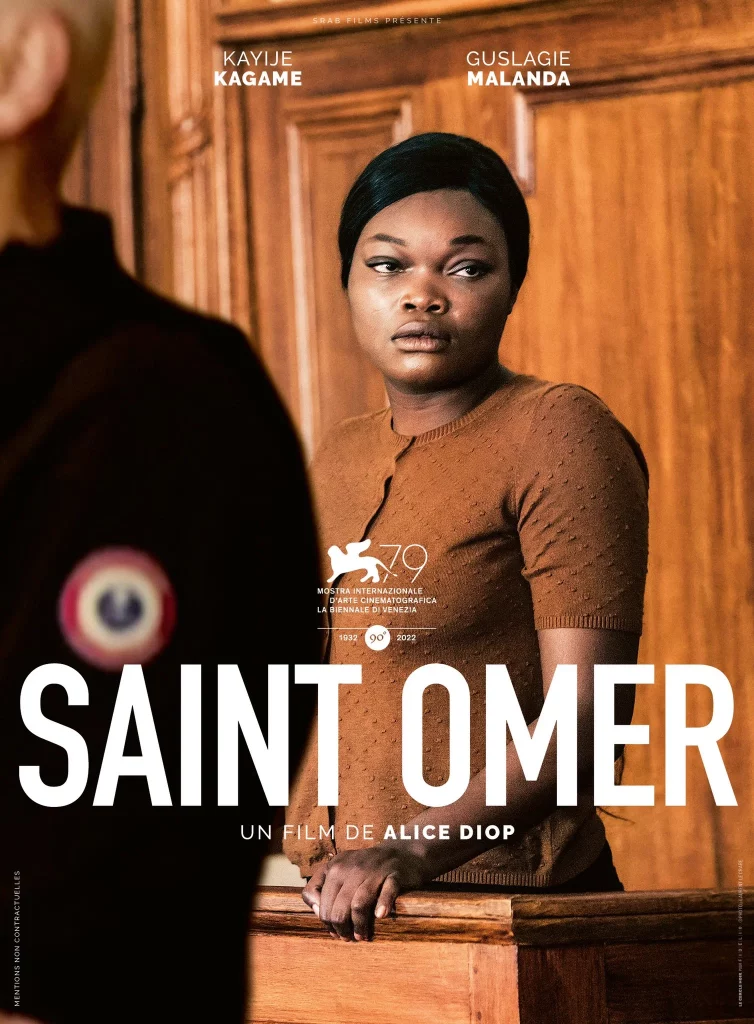

‘Saint-Omer’ won the “Grand Jury Prize” and “Best First Film” at this year’s Venice International Film Festival (although the director Alice Diop is not a newcomer to the genre, having previously made documentaries), based on a true story: the horrific case of a mother who murdered her own daughter.

‘Saint-Omer’ : the modern version of Medea behind the murder of a relative People of color, women, immigrants, multicultural background themes …… Each of them coincides with the current hot topics and trends in filmmaking, saying that ‘Saint-Omer ‘ is a very politically correct film, a good point.

However it is not speculative, the sober observation and reflection of events, the rigor of details and layers, make this simple and direct film, with profound sincerity to move the heart.

At the 79th Venice International Film Festival, ‘Saint-Omer’ ranked second in the ICS media score list and won the Grand Jury Prize and the New Director Award after the Golden Lion, and was the only French film to win the Grand Jury Prize at this year’s Venice International Film Festival. It was the only French film to win the Grand Jury Prize after the Golden Lion and the Emerging Director Award.

Technically speaking, Alice Diop, who is originally from Senegal, is not a newcomer to the film industry. Previously, she has worked more in the field of documentary film, and has a proven track record.

2021’s ‘Us’ follows regional trains through Paris and the suburbs, chronicling the lives of marginalized minorities along the coast, especially in the suburbs, and won two awards at the Berlin International Film Festival, Best Film in the Encounters category and the Golden Bear Documentary.

The 2017 short film ‘Vers la tendresse’, which also focuses on a troubled Parisian suburban neighborhood, was honored with Best Short Film at the César Awards.

Saint-Omer’, in the 79th Venice International Film Festival, is the director’s first feature-length film and the only debut in the main competition.

It is also the second black director to be selected for the main competition at Venice International Film Festival, after Steve McQueen (‘Shame’) in 2011.

Based on a real-life social event, ‘Saint-Omer’ is the story of Laurence Coly, a young Senegalese immigrant university student who is brought to trial in the small town of Saint-Omer on a murder charge. She is accused of drowning her 15-month-old baby girl by leaving her on the beach at high tide.

The young mother, who has a PhD and a reported IQ of 150, acted in such an unconscionable manner that the case received a great deal of attention from French society and the media when the trial opened in France in 2016.

The media reported the case as a social event and, in addition to being amazed that black immigrants could speak French fluently and elegantly and making a big deal out of it, attributed the case to the madness of being under the spell of African witchcraft.

The film starts with this seemingly unbelievable social event and uses a double set narrative: in addition to the main story of the court trial, the young novelist Rama, whose next work is based on the Greek myth of Medea (the witch who killed her brother for love), travels to the town of St. Omer to observe the trial and gather material for her work.

Rama is the audience’s viewpoint, watching the words and actions of the judges, lawyers, prosecutors, witnesses and especially the defendant Laurence in the courtroom.

Along with the case interrogation in-depth, we found that this sensational female murder case, far from the black and white that people imagine that simple.

It is a tightly narrated, step-by-step journey into the events and characters.

The first thing that everyone, including the judge, wanted to understand during the long courtroom trial, which lasted for several days, was: for what motive would a mother abandon her baby on a high tide beach with such cruelty?

From the beginning of the trial, we learned that the girl had a good family and educational background. Witnesses appeared one by one and told us about their experiences with the girl Laurence.

A seemingly simple fact, as information comes out of the mouths of various witnesses, the unusual birth of the baby girl and the psychological transformation of the young mother come to the surface.

The context is a little clearer, and seems to become more complicated.

It involves the girl’s relationship with her family and relatives, the girl’s relationship with older men, the girl’s relationship with French society, the girl’s relationship with herself and her deceased child ……

When a young African girl, full of ideals and studying in France, leaves her life as a foster child in a relative’s house and changes her major without permission to pursue her philosophical dreams, her life takes a turn for the worse when her angry father stops supporting her financially.

Laurence, who has no one to turn to, chooses to live with an older white man who is separated from his wife, and gives birth to her baby girl alone, ignored by the people around her.

We clearly see how a highly educated girl, even without experiencing the wretchedness of illegal immigration, but as a person of color, with the accumulation and superimposition of various factors, is forced into a social dead end and isolated from her surroundings, and how step by step she enters into her own crazy delusion and cannot get out …… Rama, a novelist as a spectator Far from being an instrumentalist.

In fact, director Alice Diop was immediately drawn to this high-profile case when she read about it in the newspaper: also from Senegal, at the same age, and even then the director had just become the mother of a new mixed-race child.

She came to the northern town alone, without telling anyone, to observe the unusual trial.

In a sense, the character of Rama in the film embeds many of the director’s own experiences and emotions.

Laurence and Rama, in and out of the courtroom, are two women from different backgrounds, both facing the transition of motherhood and living as dark-skinned women of African descent on French soil.

It was in an environment where he was invisible to the people and society around him that Laurence isolated himself into madness.

The director wants to tell us that the final result can never be simply explained by the African witchcraft reported in the mainstream media.

A French film with a colored, female subject, which in itself is rare, breaks with the prejudiced portrayal of African immigrants and their descendants in traditional European films; no longer the humble underclass, they are intellectuals, the social elite, just as Rama is a novelist who also teaches at the Paris Institute of Political Science.

The young girl on trial, Laurence, is from Dakar, the capital of Senegal. She did not grow up without material care, received a good education and had the opportunity to study in Paris, France. …… But all this does not allow them to get rid of the usual prejudices and perceptions of Western society.

In the director’s view, the fact that the defendant was the subject of media attention because of his ability to use elegant and precise French was, in a way, a form of discrimination and prejudice against people of color.

Just as the director himself, who is also highly educated, very often has to face this awkward appreciation.

Women are also well represented, from the defendant’s female defense attorney, to the female judge who listens patiently in the courtroom in search of the truth, to the mother of the defendant Laurence …… They stand in stark contrast to the male prosecutors who represent the traditional social values of righteous and straightforward accusations.

It is also a film that explores motherhood.

In the opening scene, Rama called out to his mother, running alone wandering in the night by the sea …… until the dark room lights up, we know it is a nightmare.

As the case progresses, we learn in the second half of the film that she is pregnant for the first time, growing up in a large African family, growing up with a delicate relationship with her mother, so that she is faced with the fact that she is about to become a mother, overwhelmed and unsettled, thus giving an explanation for the opening film and the dreams interspersed in the middle of the story.

How does a black woman living in France face her life and the experience of moving through her own experience of being a child as an immigrant mother?

The exploration of the mother-daughter relationship is rarely seen in African films: Rama’s estrangement from her mother, Laurence’s growing strong mother, and her deep, flesh-and-blood soul connection to her daughter, who is only 15 months old. …… What kind of mother, what kind of roots and culture she comes from, affects each other’s relationships and the way the next generation thinks and acts in relation to themselves and to society.

The film presents both a universal discussion of this and a special side of black immigration.

As a serious author film carrying the director’s mission, although the events themselves are shocking enough to tell, the images are bold and risky, not at all pleasing to the audience.

Without fantasy montages and claptrap, the director continues the experience of previous documentaries with a simple and clean style between documentary and fiction, cutting directly between the various parties in the courtroom.

In the trial scenes, calm fixed shots and long shots present judicial realism and rigor; a large number of close-ups and even high-definition close-ups focus on the faces of the characters, magnifying the faces, bodies and complex private emotions of the Black African women in European cinema, announcing their existence and exploring their hearts.

The face of the defendant Laurence, from the beginning to the end, remains almost unchanged. The whole story advances, relying more on a large number of layers of in-depth courtroom monologue testimony, and the immersively engaged audience can gradually piece together the landscape of a fatal life, imagining the loneliness and helplessness she once faced, and the lack of anyone to reach out when she fell into the abyss of madness, before the final tragedy.

The way the camera expresses itself complements the message the director wants to convey: to use the film to speak out, to change the silence of this group of people and their reality of being ignored and invisible in a society dominated by white people, and to give African-American immigrants a chance to be seen directly by the audience.

Because they have the same intimate emotions as white Westerners, their inner complexities should not always be stereotyped in profile.

In his acceptance speech at the Venice Awards, director Diop quoted American author-poet, feminist and civil rights activist Audre Lorde’s book Sister Outsider: When it comes to black women, our silence does not protect us, so tonight I want to say that we will never shut up again.

Related Post: ‘Saint-Omer’ will represent France in the 2023 Oscar competition for best international film.