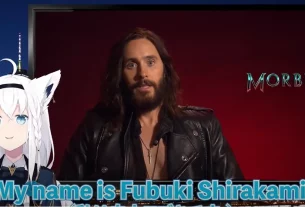

Recently, Cannes regular director Cristian Mungiu returned to the big screen and delivered another powerful film, ‘R.M.N.’.

A long scene in which local residents debate in the town hall has sparked discussion since the film was screened at the Cannes Film Festival.

The 18-minute group scene was shot to the end, with 26 actors speaking, interrupting and accusing each other from time to time in front of the camera, which triggered the long-suppressed conflicts between labor and management in the town.

The scene was greatly appreciated by well-known media reviews such as indieWire and Time Out, and was considered one of the most important movies of the year.

Cristian Mungiu is a leading figure in the new wave of Romanian cinema. In 2007, he won the Golden Palm Award at the Cannes Film Festival for ‘4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days’, followed by ‘Beyond the Hills’ and ‘Bacalaureat’. Beyond the Hills’ was also selected as one of the top 9 foreign language films at the 2013 Academy Awards, the country’s best result in this category in recent years.

The audience was also very positive.

“That 18-minute one-shot rally scene is too shocking to see a goose bumps!!!”

“A ten-minute rally scene that almost brings to life the problem of racism in Europe today. On one side is primitive and barbaric hatred and discrimination, on the other is weak hypocrisy and decency. In a day when racism prevails, freedom is absurdly like an old legend, and only immediate gain is the eternal truth.”

“The cold, bleak, gray tones of the Romanian town produce the kind of tremendous power that comes from hearing thunder in silence. Watching Cristian Mungiu’s new film after five years, I’m still struck by the lack of words.”

Complexity and Multiple Meanings

The story is based on true events and depicts the loss of labor and economic depression in the EU border town under the influence of globalization. The town, which was already home to a diverse group of people, has gradually developed xenophobia and racism, and the problem finally came to the surface on Christmas Eve when the local factory brought in low-paid foreign workers.

The film takes a dotted narrative earlier: first the boy passes through the woods on his way to school and stops abruptly, looking terrified. Then we see a slaughterhouse worker being reprimanded for using a cell phone and attacking his verbally abusive supervisor. And the woman in charge of a small-town bakery is hurting for a shortage of staff.

The man originally worked in Germany and hitchhiked back home to Romania after the accident, and we learned that the boy was his son, so it is conceivable that the content of the phone call was probably about the boy, who suddenly refused to speak.

The hero here, in addition to the children, there is an increasingly frail but solitary old father, and two women, a seemingly estranged wife, a bakery supervisor, the latter is a third party? It is not clear. Anyway, when these points are linked together into a line, the screen will know.

The man is not pleasant. Emotionally indecisive (unlike the lover who manages the bakery who broke up with his ex-husband long ago, he avoided Germany and left the house to his wife, and then came back to haunt his lover), and then scoffed at his wife for going to school with the child, sleeping with him, teaching him to knit, and so on to relieve his fears, fearing that his son would not grow up well.

However, when he was in charge of demonstrating how to bring up children, there were a lot of hints that were meant to be unspoken: the first time he sent the children to school, strangers appeared in the woods and were driven away by him; the second time there was a suspected bear infestation, he raised his gun to shoot the children to stop it, he said he was just scaring it.

The third time he took the children to learn how to make traps, row a boat, point out the mines that have stopped working, and teach them to purify the sewage for drinking. In addition to the cycle of environmental protection and livelihood, pollution and unemployment, he also informed his ancestors that they actually came from Luxembourg.

These daily routines contain strings. The two evictions (declarations of sovereignty) are aimed at outsiders and wild animals, who will become huge and obvious problems later in the film.

In addition, the heroine also said that her ancestry is Hungarian, her brother is working in Spain, together with the male protagonist’s previous self-reported family, indicating that the town was originally a multi-ethnic composition, with the accession to the European Union and economic incentives, many people left their homes to work in Western Europe, so the bakery can not hire people (and low wages are also related).

It is worth noting that when the heroine went to post the recruitment notice, the director deliberately highlighted another warning on the glass “Beware of wild animals (patterned as bears)”.

In fact, the real bear does not appear in the film, it is treated as a dangerous and aggressive animal, but the locals feel that the most dangerous is the Sri Lankan migrant workers introduced by the bakery.

Interestingly there is also an outsider in the film, a Frenchman sent by a French conservation NGO to survey the wild bear population (he represents the cost of EU membership, the impact of environmental protection on the traditional economy, and the local daring to speak out).

But the bear is also traditionally a symbol of courage and strength, so some people in the parade will wear bear head masks, and even when the locals threaten to remove workers with violence, they also dress like this.

It’s ironic that a group of people who know the pain of living in a suburban environment and who have a history of migration, do not hesitate to ostracize and discriminate against the new migrant workers who are supposed to be in sympathy with them, and bring up the old story of how hard it was to get rid of the gypsies years ago (which also makes us suddenly understand the reason for the hero’s opening rage, because his German boss called him a lazy gypsy).

When the imagery of “bears” is confused with townspeople and migrant workers, it also reinforces the complexity and multiple meanings of the film.

Long shot technology is amazing

The long shots in the movie are amazing, one shot to the end, like evidence in court to reflect all kinds of discrimination.

The scary thing is that these threats are not from some strange crazy monster, but the protagonist’s left and right friends and family, people who will watch field hockey games with you or drink and chat at community events, people you know and even grew up with.

Even priests and doctors are here to provide alarmist bias and add fuel to the fire. Of course, the long-standing low wages in the fuse’s bakery and the results of adaptation to the EU are nowhere to be seen.

It creates a realistic and shocking portrait of the crowd turning their powerlessness and anger to the scapegoat. However, in the seemingly free and meticulous composition, we also see the distracted hero only harassing his bakery lover who is unconcerned with the blind townspeople, while the wife sitting on the other side of the room is all in the eye of the beholder.

The interaction of each character seems so natural, the speeches are to the point, and the simple violence brings out the huge crisis Europe is facing today. The overall viewing process is actually quite uncomfortable, because it is so real, the core of the problem that many developing countries do not want to face, and therefore highlights how superb this film is.

The cold tone of the movie makes a cozy town look suspicious and highlights the coldness of every character in the movie.

Support Film

Cristian Mungiu takes a realistic approach to a difficult subject. In the film, an old man living alone is sent to a major hospital for a check-up, and the hero can use his cell phone to see the results of an MRI, just as the cinematography makes Romania’s new illnesses and diseases invisible.

Cristian Mungiu proves that he is still one of the most anticipated directors of all time.

Cristian Mungiu is always exposing the dark side of contemporary society with his films, depicting the current situation of society in a realistic style, sharply criticizing the system and the coldness of human nature, just like a doctor with a scalpel in his hand, calmly and precisely cutting into the lesions of the country’s society.

If power wants to destroy a place, the first thing they will do is to destroy cinema, because cinema is very close to the public and has a close relationship with the audience. If you want to be free, the first thing you have to do is to support cinema.”