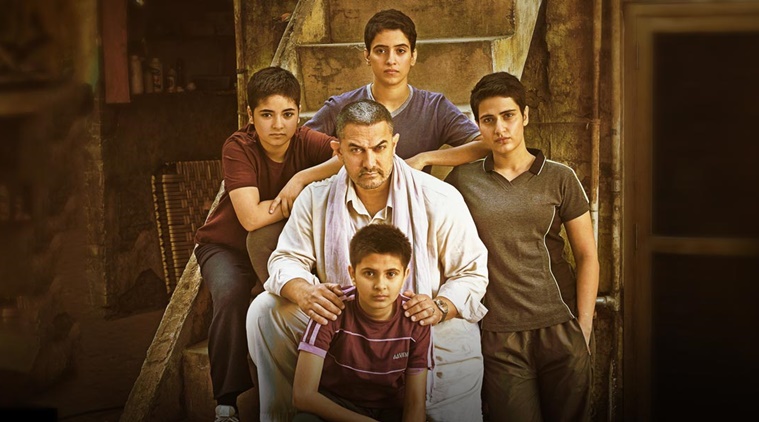

Aamir Khan stars in Nitesh Tiwari’s film based on the true story of a former Indian national wrestling champ who battles the status quo to train his two young daughters to be world-class contenders.

Director Nitesh Tiwari wisely waits until the final moments of Dangal to bring out the big guns.

Where another Indian filmmaker might have employed high-definition slo-mo and pounding orchestral blasts early on, while the popcorn is still warm, Tiwari holds off until it really matters — the high-stakes, cataclysmic climax of the film, as Geeta Phogat (Fatima Sana Shaikh) faces off against a burly Australian rival in her bid to become India’s first female wrestler to win a gold medal at the 2010 Commonwealth Games.

The film’s emotional resonance, technical artistry and compelling performances are likely to drive impressive word of mouth and healthy box office, and with any luck, a well deserved large international audience. Dangal opened Dec. 21 on a record 320 screens in North America, two days before its India release, an unusual strategy but one that could pay off for UTV Motion Pictures given the proven draw of star Aamir Khan with audiences beyond the domestic market.

Mahavir Singh Phogat (Khan) is a talented wrestler from a small town in Haryana who has won national gold medals but can’t afford to pursue an international career. He longs to pass on the tradition to a son, but when his wife gives birth to a daughter, and then another (four in all), he assumes his dream is finished.

In a charming early scene, young teenager Geeta and her little sister, Babita, come home dusty and disheveled — and victorious — after a tussle with some neighborhood boys. Their father realizes he has some potential champions living under his roof, but he and his girls will have to fight back against centuries of tradition to make it happen.

Many of Khan’s films over the decades have packed a complex, subtle message into three-plus hours of song and dance: PK (2014) explored the absurdities of religion; 3 Idiots (2009) charted the effects of stratospheric expectations on of a trio of engineering students; Taare Zameen Par (2007), which he directed, revealed what goes on in the mind of a dyslexic child; and the Oscar-nominated Lagaan (2001) reflected India’s battle for independence as seen through the eyes of a motley batch of cricket players.

Ultimately, Dangal is effective because it’s so thrilling to watch. Not only do the family scenes ring true, but Tiwari approaches the wrestling sequences with intelligence and sensitivity.

There’s sweat and dirt, to be expected. But instead of blood, bruises and machismo we see a lightning-fast match of wits and technique over brawn, enhanced by convincing performances from the film’s athletic young stars. Special mention goes to Zaira Wasim and Suhani Bhatnagar as the young Geeta and Babita, respectively; Shaikh and Sanya Malhotra as the adult Geeta and Babita; TV actress Sakshi Tanwar as Singh’s wife and Girish Kulkarni as a demanding National Sports Academy coach at odds with Singh’s old-fashioned training techniques.

Khan — a notorious perfectionist who reportedly gained and lost over 50 pounds for his role — turns in a moving performance in a complex and not-always-sympathetic role. As the girls’ coach, he forces them to wake up at 5 a.m. for a grueling daily training regimen, and when they complain, he responds by cutting off their hair — yet as a devoted father to daughters in a male-dominated society, he is fiercely protective, his displays of affection and pride that much more meaningful for their rarity.

For Tiwari and Khan (also credited as a producer), Dangal presents an indictment of a wide range of India’s ills, from its toothless national sports federation, peopled by indolent bureaucrats with neither the time nor the inclination to support the obscure sport of women’s wrestling, to the closed mindset of its small towns.

Dangal’s most pointed barbs, though, are aimed at the status of women in rural India. Singh’s home state of Haryana is known as one of India’s most backward in terms of gender equality — with a female literacy rate of just 60 percent and an abysmal record for female feticide, Haryana seems like the last place one would imagine to spawn feminist female athletes.

In a scene that takes place at a friend’s wedding, Geeta and Babita complain to the 14-year-old bride that their father is too strict and trains them too relentlessly. “I wish my father was like yours,” their friend says softly. “I’m going to cook and clean for a man I’ve never met. At least yours is preparing you for your future.”